Research a “labor of love” for physicians in early days of SCPMG

Research a “labor of love” for physicians in early days of SCPMG

The earliest days

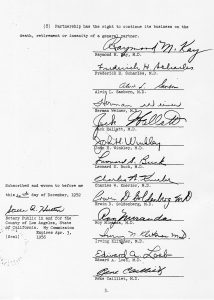

The origins of our research program can be traced back to the 1950s, when 13 physicians signed the first Partnership Agreement to form the Southern California Permanente Medical Group in 1953.

The origins of our research program can be traced back to the 1950s, when 13 physicians signed the first Partnership Agreement to form the Southern California Permanente Medical Group in 1953.

The next year, SCPMG Executive Medical Director Raymond Kay, MD, brought the growing number of research efforts under a central umbrella by creating the Research Committee (now the Regional Research Committee). He appointed as chairperson Jack Cooper, MD, an early expert in detecting prostate cancer.

“For the next few years, Dr. Cooper would be a one-man research committee and Institutional Review Board, years before we had an official IRB. He approved all research projects and delegated funds,” recalled Samuel O. Sapin, MD, SCPMG’s first pediatric cardiologist and one of a small handful of physicians who received funds for research projects in those early years.

“For the next few years, Dr. Cooper would be a one-man research committee and Institutional Review Board, years before we had an official IRB. He approved all research projects and delegated funds,” recalled Samuel O. Sapin, MD, SCPMG’s first pediatric cardiologist and one of a small handful of physicians who received funds for research projects in those early years.

The Research Committee’s budget grew from an initial $10,000 in 1954 to $54,648 in 1959 (equal to $559,271 in 2023).

Research finds an official home

In 1963, KPSC’s first research department — then called the Department of Education and Research — was established. Its primary function was to track and manage the research budget. By 1969, the budget had increased to $230,000, the equivalent of $1.9 million in 2023. Those funds supported physician-led research focused on topics that arose from clinical practice.

“We often refer to the 1960s as the days of giants because these individuals stood tall from the norm, and they represented people who went against the grain and did not follow the path of least resistance. For the physicians of this era, research was truly a labor of love,” said authors John J. Sim, MD; Kristen Ironside, MA; and Gary Chien, MD; in a 2019 article published in The Permanente Journal.

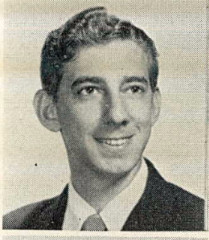

One of the physicians engaged in research at the time was Irving Rasgon, MD, a physician at the Kaiser Permanente Los Angeles Medical Center. Much of his research focused on the importance of screening to detect colorectal cancer.

One of the physicians engaged in research at the time was Irving Rasgon, MD, a physician at the Kaiser Permanente Los Angeles Medical Center. Much of his research focused on the importance of screening to detect colorectal cancer.

His son, Scott Rasgon, MD, who also became an SCPMG physician and researcher, recalls that his father and his colleagues were motivated by their own curiosity and often worked on research on their own time.

“Physicians said to themselves, ‘This is interesting. I’ll do a study,’” he said. “Statistics weren’t that sophisticated … My dad pulled his data from paper charts, often working at home. This was in the days before HIPAA. It was very informal.”